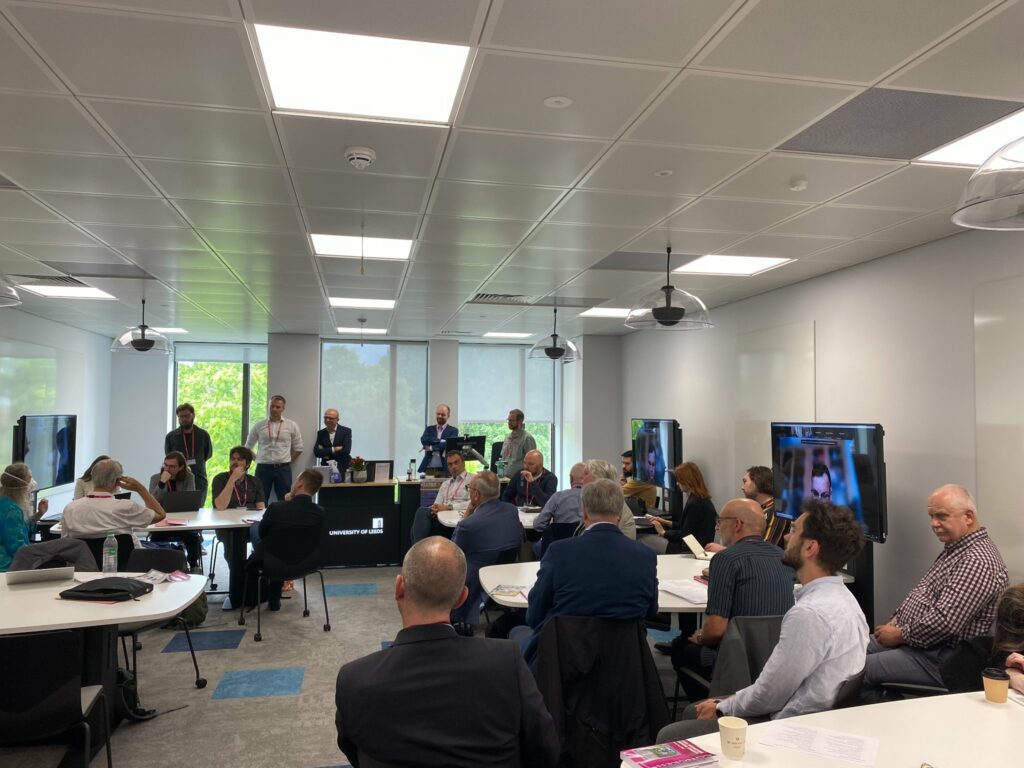

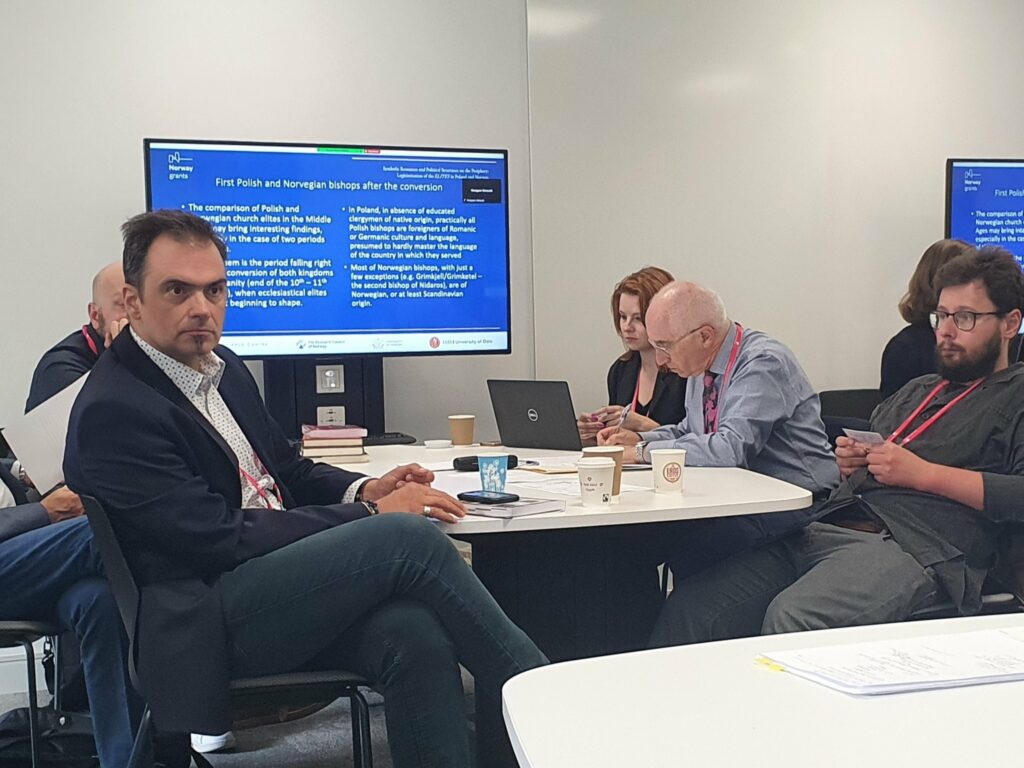

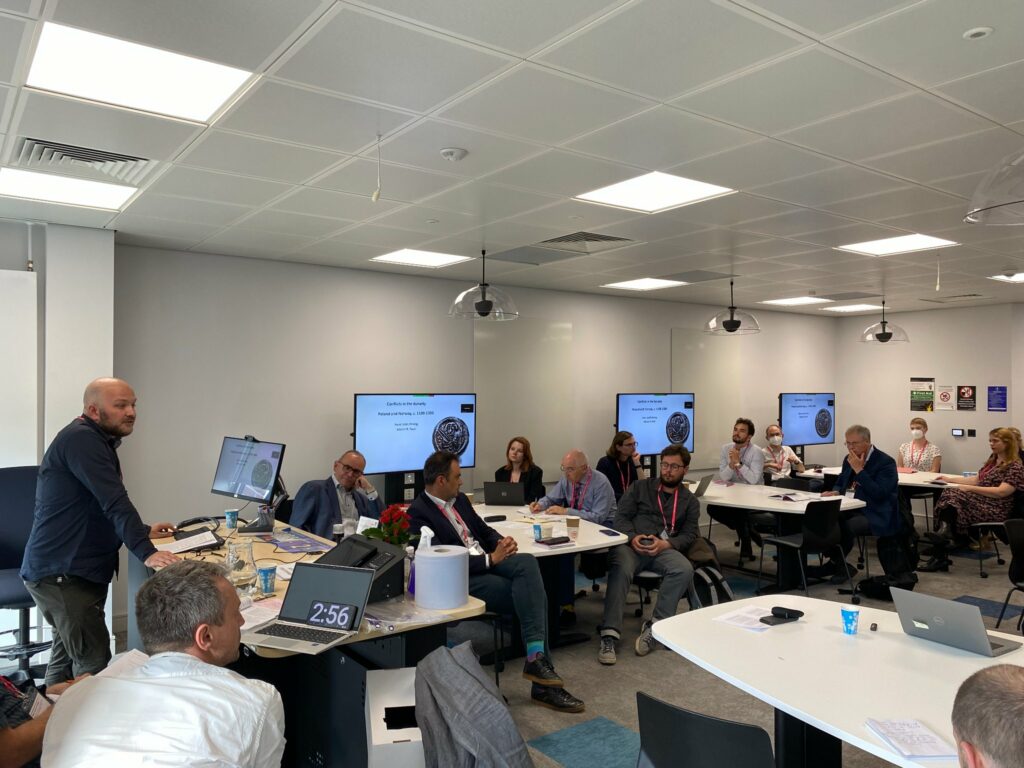

This year at the IMC our team members presented their research in three sessions ‘Elite Legitimacy on the Borders of Latin Christendom: Poland and Norway, 1000 – 1300’ and one round table discussion.

We invite you to browse the IMC programme.

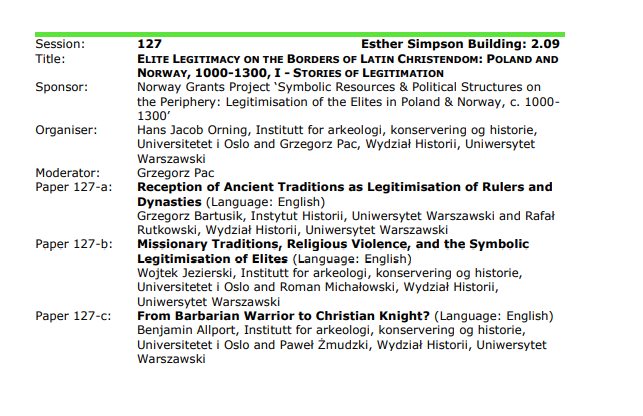

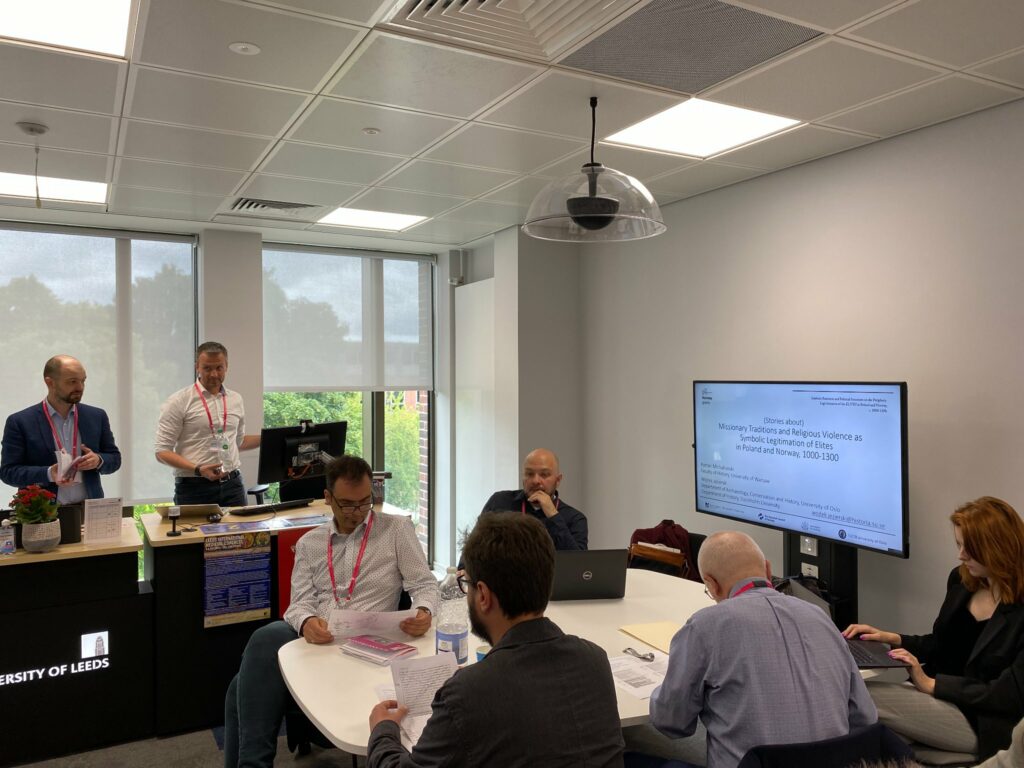

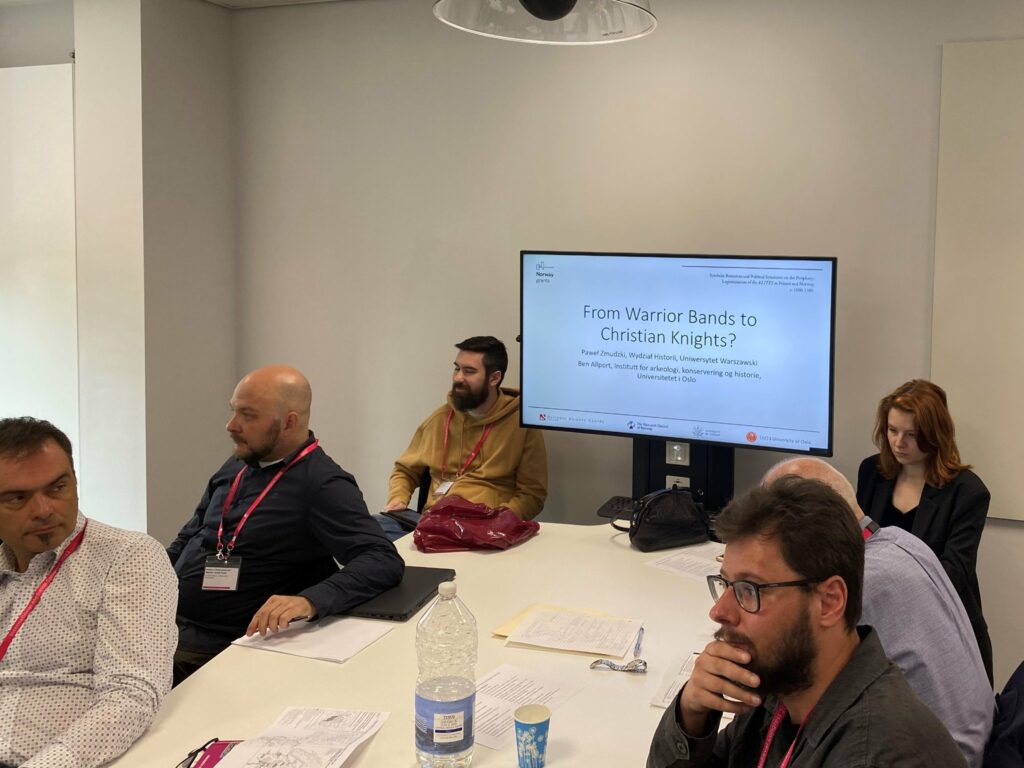

127: Stories of Legitimation, organised by Hans Jacob Orning and Grzegorz Pac, with the papers by Grzegorz Bartusik & Rafał Rutkowski, Wojtek Jezierski & Roman Michałowski and Benjamin Allport & Paweł Żmudzki.

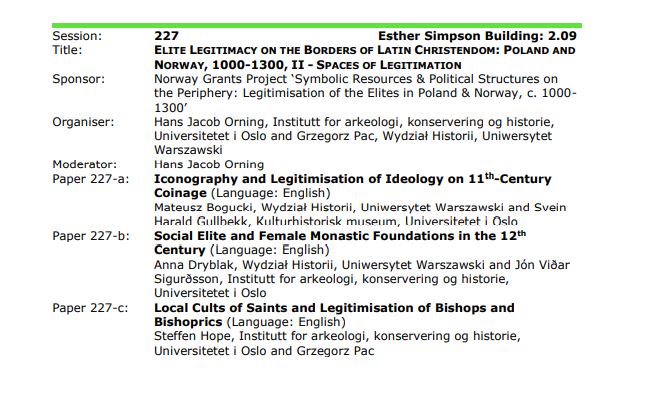

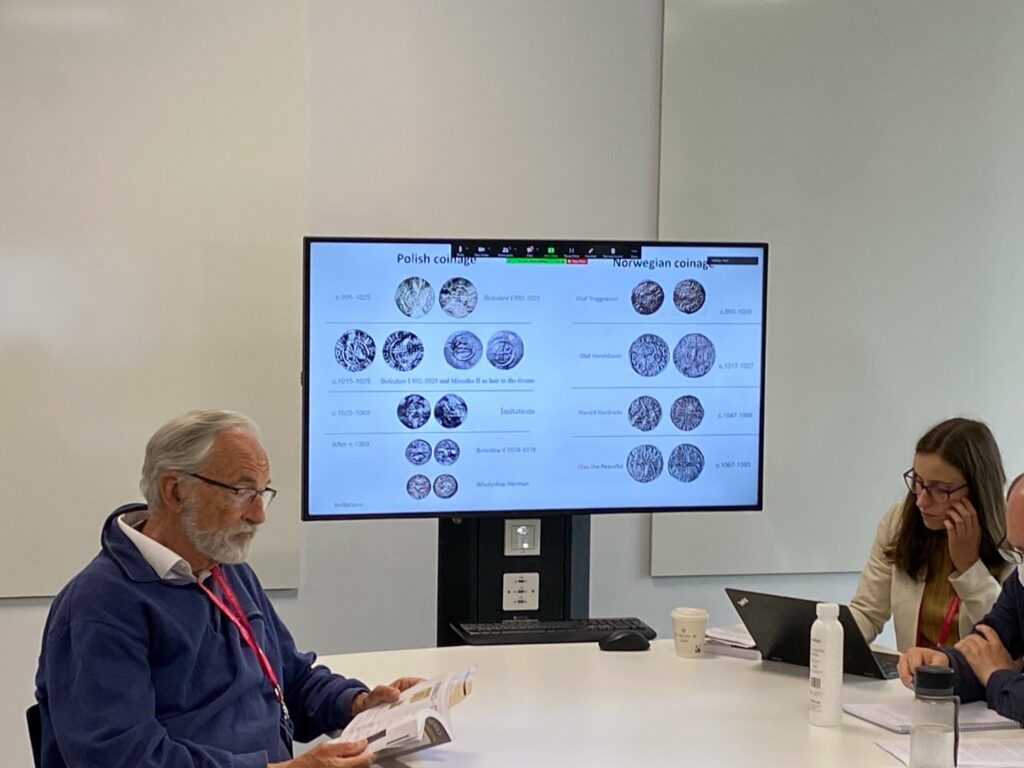

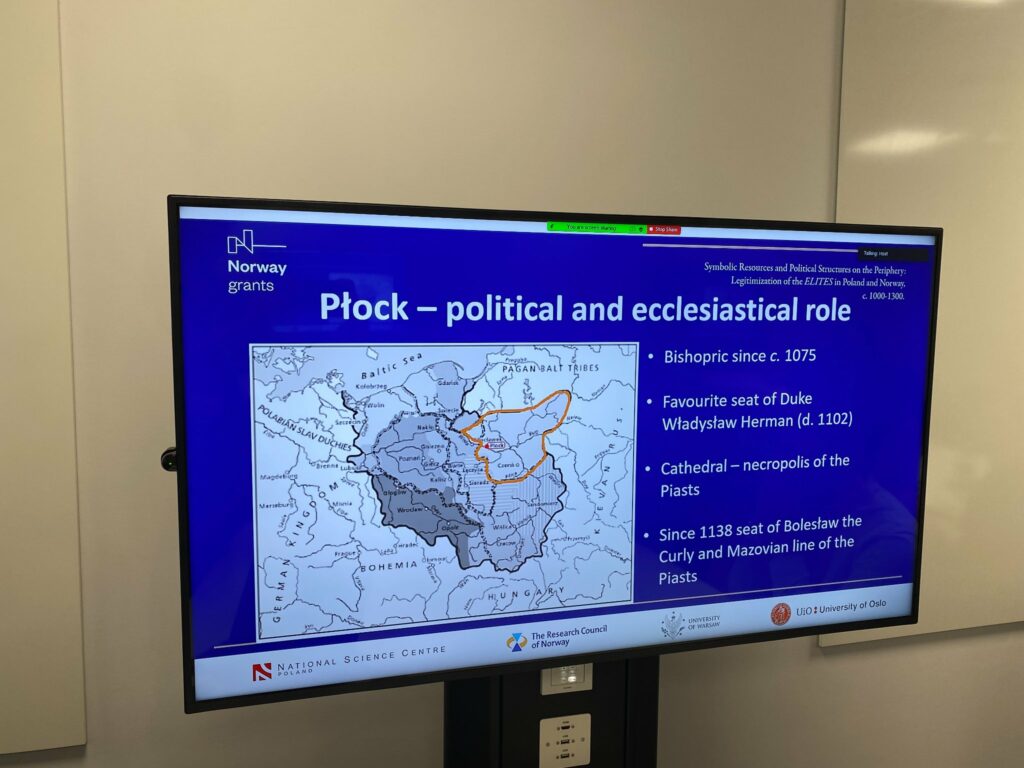

227: Spaces of Legitimation, organised by Hans Jacob Orning and Grzegorz Pac, with the papers by Mateusz Bogucki & Svein Harald Gullbekk, Anna Dryblak & Jon Viðar Sigurðsson and Steffen Hope & Grzegorz Pac.

327: Struggles for Legitimation, organised by Hans Jacob Orning and Grzegorz Pac, with the papers by Jerzy Pysiak & Krzysztof Skwierczyński, Zbigniew Dalewski and Hans Jacob Orning & Marcin Rafał Pauk.

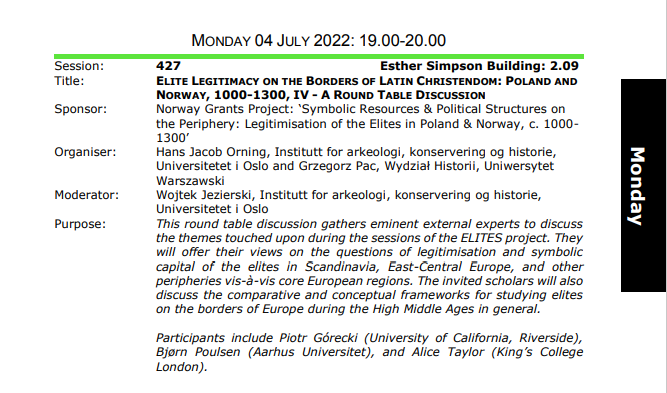

There was also a round table discussion organised by Hans Jacob Orning and Grzegorz Pac, moderated by Wojtek Jezierski, with the participation of Piotr Górecki (University of California, Riverside), Bjorn Poulsen (Aarhus Universitet) and Alice Taylor (King’s College London).

We have received a very interesting feedback regarding comparative history, with a special emphasis on methodology and the problem of understanding the periphery. We invite you to browse the photos from the event and to read the sketch of a text by Alice Taylor.

General reflections – what’s going on here.

First, how much I’ve appreciated all papers being comparative. Really different. Normally you have one case study then another paper on another – but having the joint presentation of papers and the wrestling of how they can be compared has been really helpful.

So the project avowedly continues the move away from Bartlett’s 1990s Europeanisation and also problematise the more ‘similarities’ approach to European political culture – e.g. Björn’s Paths to Kingship. Also significance of comparing secular and spiritual elites together. Which is important given the long-held dominance of the edifice of the modern state, which projects backwards a distinction between church and state onto categories of regnum et sacerdotium.

But doing something more substantive about the Wider sociological question of how did they get away with it? Perhaps not entirely obvious, but the idea of legitimation doesn’t just mean legitimation to each other but legitimation over those they exercised power and authority. Question posed with such vehemence by Tim Reuter – and worth stating more specifically:

“The members of the elite strata of the societies we study as medievalists … were mainly concerned with competition amongst themselves to increase or maintain their share in the fruits of domination. It was in this competition that they appear to us and seem to have appeared to themselves to have invested the bulk of their time, energy and resources; the global domination of these strata over the rest of society was, so it seems something which largely took care of itself … what we have to do now is to move from banal generalisations to investigation of the specific forms taken by this automatic and largely unchallenged domination in medieval Western Europe’. How did they get away with it: and we have seen a mixed media approach today: text, material culture, visual imagery.

And where did the raw material come from to get away with it? Move away from a singular cosmopolitan culture (France, which stretches outwards – core periphery), so to speak, multiple centres of cosmopolitanism, with multiple and changing models.

Comparison between these two regions and how they compare to Scotland:

A number of papers have stressed the difficulties of this comparison, in part because of the (different) difficulties of the surviving evidence, and how representative it is of change (is the Gallus Anonymous). And also that the evidence we do have is indicative of claims about change – and not necessarily descriptive of social reality – not the point. So one thing that occurred to me is to do the thing that Wojtek was like no we are not going todo this – is the archival survey- being explicit about the structures of power and accidents of survival which give us what we have. In Scotland most of our twelfth-century material is mostly late medieval predominantly monastic archive-creation. What can we do with that?

Comparison not just across polity but also across type of source: Not look for unity of imagery: importance of saints in some sources (e.g. sagas) but not coinage (not until the 16th century): need an explanation / hypothesis for that difference? (E.g. in Scotland, seals are the way in which particular images – e.g. Columba minority seal and Andrew under the guardians). But not coins – like in Norway in Scotland, Scottish coins not the only legal tender until the fourteenth century. Importance of local saints in Norway but less so in Poland until later? Vs Scotland, clear examples of local saints – with the universalising ones of the 12th century – in which Scotland is much more at the front of what is cool monasticism, for example.

Very important in comparisons, therefore are Wojtek’s and Roman’s ideas about different styles of political culture. Different Dominant ideas are stressed – why do we have these differences- why is the idea of the Rex iustus so key in Norway, and less stressed (although assumed) in Poland? (And indeed in Scotland – although you obviously have the reputation of David I? ). Comparative vocabularies of authority. Benjamin and Pawel’s ideas about warrior to knight, as well as the difficulties in thinking in those terms. But this does bring to the fore the question of the stability and universality of Latin vs vernacular terms. Thinking in Latin? What are the vernacular words which get kept and survive through Latin – vs Norway where were have a vast richness of vernacular material? And when words are kept in Latin? Why? And How? What about transliteration, transposition, etc? Scotland – idea of territorialisation as the dominant idea in the later twelfth century – new Latin vocabulary – vs other words that are kept, still have relevance, and have such strong legal meaning that they resist translation.

III: Importance of comparison – two-way comparison. Does this over-emphasise difference? Sociological importance of three. What and why might another polity or elite authority be included and on what justification (and would it be one of the ‘centre’, perhaps the papacy…)? Are we looking at time-lags? Probably not. Is it on the so-called periphery that the aims of the ‘centre’ are most clearly realised—need a centre-periphery sense in order not to illuminate the periphery (as in the Europeanisation model) but to illuminate the centre, so particularly important for a more political, critical history of the papacy? Equally, to what extent are many choices in some way structured by wider geopolitics and institutional structures? Question of competitions against more powerful neighbours??? Poland as part of an imperial tradition. Polish history – subsumed by idea of translatio imperii. Carolingians, Ottomans Piasts.

Cf. Scotland where idea of antiquity gradually avoids the idea or does not make dominant of English translatio imperii, even if there is the raw material to do so (and indeed, this was done in the thirteenth century)]. And Steffen and Grzegorz idea that actually one potential explanation for the lack of native cults in 12th century Poland might be because it has a clear disocesan structure imposed; and this is also a question that resonates for the Scottish material- the extent to which you have new diocesan provinces in the 11th/early 12th centuries which plugs the Scottish church into wider communication networks.